Chapter 2: Palais Wilson, the memory and hostage of Geneva

The imposing sandstone building by the lake known today as Palais Wilson, wich has served as the headquarters of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights since 1998, is the oft- revived corpse of an unlucky structure. Built between 1873 and 1875 by the Genevan architect Jacques-Elisée Goss (1839–1921), whose legacy includes the Geneva Opera, it was originally designed as a luxury hotel for wealthy Europeans touring the continent.

Its promoters, the hoteliers Alexandre Rufenacht and Charles-Frédéric Aldinger, envisioned it as a right-bank companion to the prestigious Metropole hotel, built 20 years earlier by Joseph Collart on the Grand Quai, behind the Jardin Anglais. At the time, the epitome of elegance was French Neo-Renaissance architecture: two symmetrical side-wings with mansard roofs, flanking a central wing topped with a roof lantern; spacious interiors heavily decorated with marble, mouldings, paintings, and wallpaper.

The original Hôtel National built between 1873 and 1875 by Jacques-Elisée Goss

© Bibliothèque de Genève

The expense of such a building stretched the developers' budget thin, even after substituting faux-painted marble and wood for the real thing. The unstable terrain of the embankment, built on land reclaimed from the lake, further inflated construction costs, exceeding the partners' resources. Two months before the building was finished, a deeply depressed Aldinger threw himself out of a window.

Inaugurated in 1875, the Hôtel National failed to win a regular clientele. It was hindered by its location outside the city centre, in the somewhat disreputable area of Les Pâquis (from "pâturages", or pastures), which marked the vague border between city and country, and was occupied by a mixed, constantly shifting population of farmers and fishermen. Two years after opening, the hotel was declared bankrupt and its creditor, the Federal Bank, sold it at auction for just 700,000 francs.

Hôtel National in 1920 after the first renovation by Marc and Jean Camoletti

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

Its luck changed shortly after the end of the First World War, when a hotel magnate from the Côte d'Azur decided to modernize the hotel with the help of an up-and-coming star of architecture: the elevator. Marc Camoletti and his son Jean, the architects of Geneva's Musée d'art et d'histoire, oversaw the renovation. Rearranging the hotel's layout completely, they moved the reception areas from the ground and first floors – where they were traditionally located before the elevator age – to the top of the building, and added loggias to the mansard-level bedrooms to allow sweeping views of Mont Blanc. The refurbished hotel, due to open in 1920, would offer 146 rooms, 79 of them with private bathrooms.

It was still under renovation when the League of Nations' secretary-general, Sir Eric Drummond, visited Geneva in August 1920, searching for premises for the newly minted organization, and took a liking to it. The League bought the hotel for 5.5 million francs, and the same architects were commissioned to adapt it to its new purpose. They turned the bedrooms into offices, the reception rooms into meeting rooms, and the service areas into storerooms and archives. In 1924, after the death of the American president to whom the League and Geneva owed so much, the Hôtel National was renamed Palais Wilson, and the Quai du Léman in front of it renamed Quai Wilson.

Hôtel National in 1920 after the first renovation by Marc and Jean Camoletti

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

The former hotel was merely a way station for the League: in 1926, it announced an architectural competition for a "Palace of Nations" better suited to its requirements. Meanwhile, the Palais Wilson became more and more crowded. In 1931, the Council of the League decided to build a pavilion to host the first Conference on Disarmament, scheduled to take place in Geneva in February 1932. They chose the Genevan architect Adolphe Guyonnet, unknown to modernist circles at the time. His square metal and glass extension at the back of the Palais Wilson, finished in under six months (the building no longer exists), was probably the first instance of pure, elegant modernism in Geneva.

The League of Nations stayed in the Palais Wilson until 1937, when the Palace of Nations opened on the grounds of the Ariana park. After the League's departure, the building again faced an uncertain future. The hotel industry expressed little interest, given the tense global situation at the time. For lack of a better solution, the Swiss government and the canton of Geneva bought the Palais Wilson to house an international centre, followed by various federal and cantonal government offices. The historic building had been saved, but its lustre was fading.

The Disarmament Pavilion in 1932

© United Nations Archives at Geneva

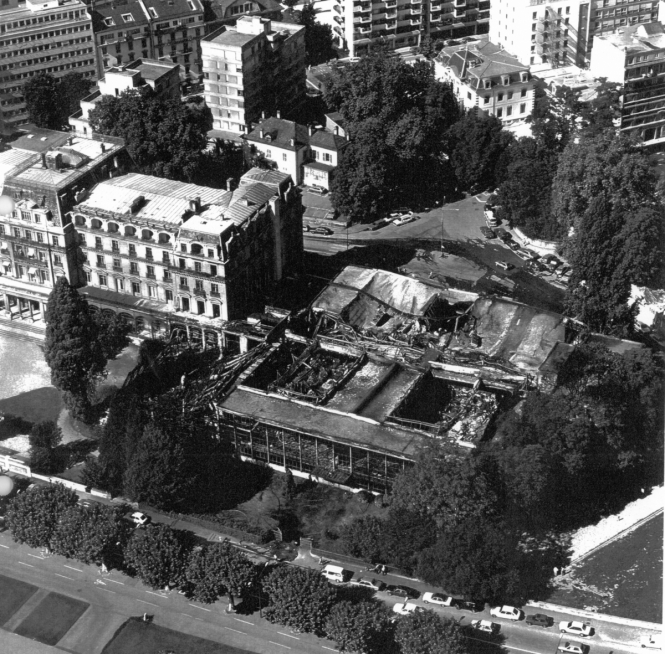

A series of swaps in 1966 and 1967 transferred ownership to the canton, then the city. For a while, it was home to the University of Geneva's Institute of Educational Sciences, led by Jean Piaget. The European Centre for Culture, Centre for Contemporary Art, Fondation des archives européennes, and Association des professionnels du cinema occupied the rest of the building. By then, the ill-fated former hotel was subsiding into the embankment; the sandstone façade was crumbling; pigeons had colonized the loggias. In 1985, a fire destroyed the entire ground floor of the south wing. Two years later, in August 1987, the disarmament pavilion – used as a convention centre since 1956 – went up in flames.

Around the same time, the city government began discussing an ambitious project with Albert Tamman, the owner of the President hotel next door. It involved transferring the lease on the Palais Wilson and the podium to Tamman's company, Groupe Centre Président-Wilson; renovating the building as a luxury hotel; building a much-needed convention centre under the raised podium in front of the structure; and tearing down the President Hotel, built in 1963, to make way for a commercial and services building.

The euphoria of the late-1980s emboldened developers to dream big. Tamman and his partners put 200 million francs on the table. A group of architects, led by Bernard Erbeia, drew up the plans. But the project was highly sensitive. Christian Grobet, the Councillor of State in charge of public works, wary of the ultimate fate of Palais Wilson, stated: "As long as I remain head of the Public Works Department, I will never sign an authorization to demolish this historic architectural landmark."(1) In 1990, the citizens of Geneva nonetheless voted to transfer the building's lease.

The Disarmament Pavilion after the fire in 1987

© FIPOI

The Gulf War killed the project. Investors grew fearful; tourist numbers fell. Tamman surrendered the lease. The city of Geneva resumed its hunt for a new buyer.

A solution materialized in 1992. Following the Earth Summit in Rio, the Federal Council — keen to bolster Switzerland and Geneva's position in the conversation on sustainable development — decided to buy the Palais Wilson, aiming to group the world's main environmental organizations together under one roof. Some already had a presence in Geneva, scattered around the canton. Those recently created in Rio could join them. The architects who had been hired to design the luxury hotel were now asked to draw up plans for a "Maison de l'environnment", with a total floor space of 6,077 m2, comprising offices and meeting rooms for 400 people. Geneva donated the leasehold on the building.

However, renovating the Palais Wilson would be extremely expensive. Was it worth it? The architectural community tended to disagree in principle, as it robbed them of an opportunity to showcase their talent and skill in such a prime location (2). But the alternatives they proposed failed to win over Geneva's die-hard architectural conservationists.

Meanwhile, the Swiss government was in a hurry. Germany and Spain had pulled out all the stops in a bid to attract the organizations created in Rio; buildings were already available in Bonn and Seville. In the face of such fierce competition, renovating was the quicker solution. Parliament approved a credit of 75 million francs to start renovation (3) — five million short of the 80 million requested by the Federal Council (4). The federal councillor Otto Stich came in person to lay a symbolic first stone in 1994.

But once again, circumstances prompted a change in direction. By 1997, it was clear that Geneva was not destined to be the hub of the UN's environmental protection mission. The Commission on Sustainable Development, the main strategic body, was based in New York, while the Convention on Climate Change was in Bonn. In 1996, his last year as UN secretary-general, Boutros Boutros-Ghali chose to locate the headquarters of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) in Nairobi, Kenya.

The orginal staircase and its skylight

© Luca Fascini / FIPOI

By then, the Palais Wilson's structural stabilization was almost complete; the central wing had been shored up by driving 600 stakes through the moraine of the embankment to the bedrock of the ancient Rhône glacier. To restore the building to its initial state, the loggias added by Camoletti were removed and replaced by Goss' dormer windows; the façades were stripped of later additions; the galleries facing the lake were returned to their initial function as porticos; the architects installed heat exchangers that pumped water from 300 m below the lake's surface, a state-of-the-art technology at the time; offices were created as needed with the help of plasterboard walls and raised floors; and an extension housing two conference rooms of roughly 100 seats each, complete with interpreters' booths, was added to the north wing.

The aim was to restore the Palais Wilson to its original state rather than renovate by combining old and new elements, as had been done, for instance, for the Parliamentary Union building in Grand-Saconnex. Significant efforts therefore were made to reproduce the original decor, whenever possible, based on the surviving traces. Where none was available, the architects refrained from invention. Restorers painstakingly recreated the "real" false marbles; the flower-stencilled walls of the grand central staircase bloomed anew under the expert hands of skilled artisans; parquet floors were repaired. Light fixtures were reproduced based on existing images, as in the Salon des Dames, while everywhere else, including the central foyer and hallways, contemporary fixtures were specially designed. Skilled artisans – from wrought-iron craftsmen and glaziers to carpenters and stonemasons – toiled alongside the technicians connecting the mother ship to the electrical grid and telecommunications networks. It fell to Geneva State Councillor Philippe Joye to make the final decision on the façade's colour: he opted for red.

The corridor and its “real” false marbles

© Luca Fascini / FIPOI

It was then that the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights asked the Swiss government for premises better suited to its needs than the cramped quarters in the Palace of Nations, which the organization had occupied since its creation in 1993. The UN's new secretary-general, Kofi Annan, suggested the Palais Wilson. The Federal Council immediately agreed.

The building's entire history spoke to the significance of human rights — those same rights that would soon thrust Geneva to the centre of the global political stage. But first, a few more modifications, moves, and adjustments were needed. The Centre for the Environment and Sustainable Development was rehoused in a building in Châtelaine. Finally, on 5 June 1998, the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mary Robinson, moved into the Palais Wilson with her staff.

But the story doesn't end there. The High Commission has grown from 400 employees to almost 700. Overflow staff are housed in a rented annex on avenue Motta. There is talk of moving part – or all – of the Office's staff back to the Palace of Nations, home of the Human Rights Council Room, with its chaotic ceiling by Miquel Barcelò. If so, will the former Hôtel National once again acquire a new user, after serving almost every imaginable purpose?

A survivor and witness to the city's fortunes and misfortunes over the past three centuries, this grand old building — now restored to its youthful appearance — stands as the continually updated memory of a Geneva that is both host and hostage to the world (5).

Details of the painted wall of the main staircase

© DR

Details of the painted wall of the main staircase

© DR

(1) La Suisse, 10 January 1988.

(2) As they already showed in 1988, see Ingénieurs et architectes suisse, n°7, 23 March 1988.

(3) Federal Council Message to Parliament 20.10.1993, Feuille fédérale 1993 vol.4, 21.12.93 pp. 431-458.

(4) FF 1994, vol. 2, 15.06.1994 pp. 681-682.

(5) Host and hostage both derive from the Latin verb "hostire": to return like for like, to recompense.